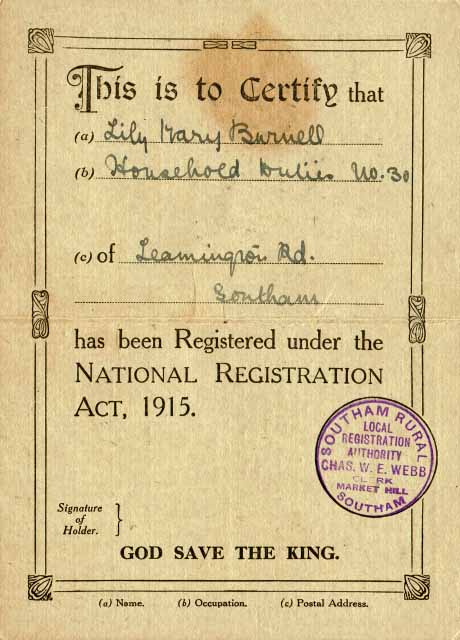

Lily Burnell

In the group picture of VADs Lily looks more confident and very smart in her uniform standing third from the left on the back row. Scarcely out of school when war broke out these young girls trained in

Work at the hospital was unpaid so Lily’s family had to make sacrifices sparing her from the tasks in the home. For a young woman it was a challenge, something totally new and perhaps an adventure to don a uniform and join her ex-school pals in the demanding regime at the hospital. Every six weeks or so she would have seen a new intake of injured men – lonely, confused or simply grateful to be out of the sound of gun fire – arrive for rehabilitation and treatment. The most severe medical cases did not come to the auxiliary hospitals, but nevertheless she would have nursed amputees, head injuries, and helped care for men whose minds were never fully to recover.

There was constant worry too at home when raw notices came telling of the injuries of her brothers in battle. One brother, Victor, was injured to the head and a piece of shrapnel came out from the back of his neck long after he was demobilised.

After the war Lily returned to looking after the family at home. She married a Southam man, Jack Tyler, in 1927. Both aged thirty, they lived with her parents in the two jasmine-clad thatched cottages which, at some point were knocked into one. Here their two daughters were born and raised.

Lily’s husband Jack was a carrier and later a factory worker. But Jack had been injured and gassed in the war and his

Mrs Mary Bicknall and Mrs Cissie Isom

looking at family pictures

and remembering their VAD mother

and soldier father

Jack and Lily are both remembered with pride by Mary and Cissie (pictured here). Jack was a soldier mentioned in despatches for bravery under fire. Their mum Lily too was made of stern stuff and whilst both her daughters marvel that she never spoke of her contribution to the war, they remember that she could be quite adamant about other matters! Jack died aged sixty four and Lily lived to be eighty. She took many happy holidays and gregariously enjoyed the company of relations and friends.