Southam in WW1

Centenary Archive

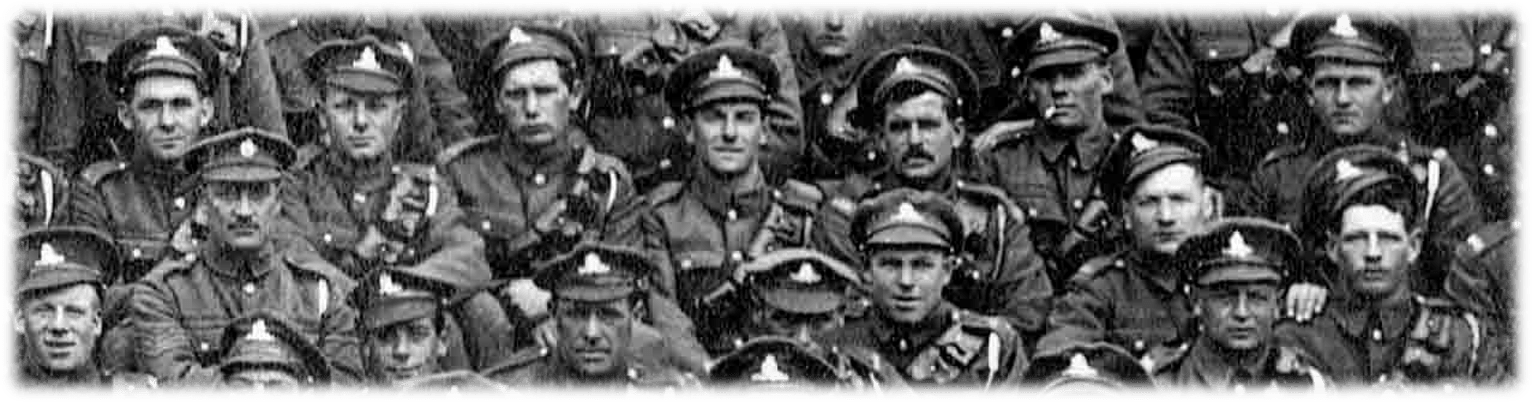

Honouring those who died and all who served

Chief Armourer Frederick William Court (340995)

In September of 1914 the first man from Southam to lay down his life was drowned in the cold waters of the North Sea. Frederick Court was serving as Chief Armourer on board HMS Aboukir when at 6.20 am on the morning of 22nd September 1914 she was torpedoed and sunk by submarine U9. Three days later the admiralty issued a list of the 527 on HMS Aboukir who had perished.

Frederick’s family background is unusual for a Southam resident. Both Frederick (b.1874), and his wife Emily Sarah (b.1880), came from north Somerset. They were married in Devon in 1905 and their eldest daughter was born in Exeter in 1907. Frederick had been in the Royal Navy for 19 years and the couple appear to have moved house before 1909 when their second daughter Evelyn was born in Southam. Emily’s whole family had moved for her father, Mark Taylor, became Gas Works Manager in Southam. They lived together in a fair sized house, the Gas House on Welsh Road. A son was born to Emily and Frederick on 18th August 1914, whom he never saw. Fred Court was baptised in Southam on 25th October 1914 a month after his father lost his life at sea.

After Frederick’s death Emily gave her address as next of kin on separate documents as 24, Stoneleigh Road, Kenilworth and also 47, Abingdon Street, Burnham-on-Sea. Here she settled for the 1939 pre-WW2 survey finds her at this address with her sister Ada, and her second daughter, Evelyn, who is listed as ‘incapacitated’. Emily did not remarry.

Frederick’s death is recorded on the memorial at Chatham and on the Southam War Memorial, so his connections with the town were strong. In September 1917 the following appeared in the In Memoriam columns of the Leamington Courier

‘In loving memory of my dear husband’.

Three years have passed since that sad day. While on the North Sea he was taken away

He was out to protect us one and all, But now he has answered his country’s call.

A lot is known about the sinking of HMS Aboukir. A brief summary follows.

On the morning of 22 September HMS Aboukir and her sister ships HMS Cressy and HMS Hogue were all sunk by one submarine whilst on patrol off the coast of Belgium, in an area known as the Broad Fourteens. As Alan Griffin has pointed out, the cruiser was hit ‘behind the first funnel between the first and second boiler rooms and ripped out the bowels of the ship from the keel to the upper deck. Within a few minutes Aboukir was floating upside down and sinking, having got away only one boat.’ The German submarine, U-9 was commanded by Otto Weddigen. Alan Griffin cites Weddigen’s account:

I climbed to the surface to get a sight though my tube of the effect, and discovered that the shot had gone straight and true, striking the ship, which [I] later learned was the Aboukir, under one of her magazines, which in exploding helped the torpedo’s work of destruction. There was a fountain of water, a burst of smoke, a flash of fire, and part of the cruiser rose in the air. Then I heard a roar and felt reverberations sent through the water by the detonation. She had broken apart, and sank in a few minutes. Her crew was brave, and even with death staring them in the face kept to their posts, ready to handle their useless guns, for I submerged at once.

I climbed to the surface to get a sight though my tube of the effect, and discovered that the shot had gone straight and true, striking the ship, which [I] later learned was the Aboukir, under one of her magazines, which in exploding helped the torpedo’s work of destruction. There was a fountain of water, a burst of smoke, a flash of fire, and part of the cruiser rose in the air. Then I heard a roar and felt reverberations sent through the water by the detonation. She had broken apart, and sank in a few minutes. Her crew was brave, and even with death staring them in the face kept to their posts, ready to handle their useless guns, for I submerged at once.

The patrol was nick-named (possibly by the Germans) ‘live bait’ for the older slower vessels had little chance to manoeuvre effectively and the Admiralty had failed to take into account the threat of submarines. (see www.livebaitsqn-soc.info for information and ongoing research into crew members).

At 06:20 the torpedo was fired at Aboukir and after 25 minutes she capsized and five minutes later sank. Only one boat was launched because of damage caused by the explosion and the failure of steam-powered winches needed to launch them.[1]

The Cressy and the Hogue both stopped to attempt to rescue survivors and they also were hit. Life jackets had not been issued and few life boats were carried. In all 837 were rescued but 1,397 men and 62 officers died. The action that morning, one of the worst disasters in British naval history, shook public opinion in Britain and damaged the reputation of the Royal Navy.[2]

[1] Massie, Robert K, (2004) Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (Jonathan Cape)

[2] Corbett, J.S. (1938 repr. 2009) Naval Operations History of the Great War based on Official Documents (Reprint Imperial War Museum)