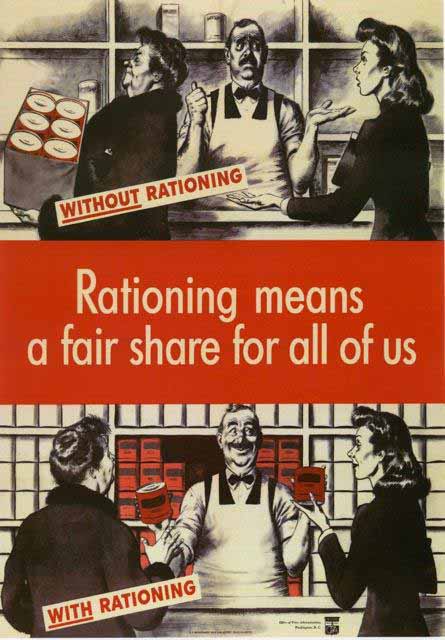

Christmases during and just after World War II were far removed from the excesses that characterise the celebration today. All of our lives were governed by the rationing restrictions imposed early in the war, some of which remained in force until 1954. (I can still see my Dad carefully slicing a Mars bar into five equal portions.)

At school I remember making paper chains to take home and I painting a jam jar as a present for my Grandad to keep his spills in for lighting his pipe. The only Christmas party I remember going to was at the Boys’ School on the last day of term. The food on offer was, as I recall, egg or paste sandwiches and lots of jelly and some small cakes. We took our own plates, cups and cutlery which were identified by coloured Sylko thread. The ‘games’ at the party went under the names of ’the treacle-bun eating’ and something that had less frivolous connotations, ‘blind-fold boxing’.

At school I remember making paper chains to take home and I painting a jam jar as a present for my Grandad to keep his spills in for lighting his pipe. The only Christmas party I remember going to was at the Boys’ School on the last day of term. The food on offer was, as I recall, egg or paste sandwiches and lots of jelly and some small cakes. We took our own plates, cups and cutlery which were identified by coloured Sylko thread. The ‘games’ at the party went under the names of ’the treacle-bun eating’ and something that had less frivolous connotations, ‘blind-fold boxing’.

In those days many folk kept a few hens and a pig, but with the approach of Christmas the poor old porker’s time ran out. He would be turned into pork pies, chitterlings, braun, trotters and sundry other unmentionable dishes which made a welcome addition to the Christmas fare. My Dad was a baker at the mill and he was frequently asked to bake large family pork pies and other items in the bread oven. Many were his stories of the culinary disasters he was witness to when he opened the oven door.

One Christmas, the Vicar of Long Itchington, a red-faced Irishman by the name of Revd Astrop, arrived at the bakehouse with a large turkey for Dad to cook. We three young lads had seen turkeys but had never tasted roast turkey. When it came out of the oven plump and golden, Dad said “Do you want a taste?” You bet we did. Without further ado, he turned the turkey over and carved a generous slice for us to sample before placing the bird right way up on the Vicar’s willow pattern serving dish. “He’ll never know” said Dad and if he did find out he never mentioned it.

Presents were rarely memorable, although one year my Dad gave me and my brother a wooden model aeroplane carved by a German Prisoner-of-War. One of our most treasured presents was a little battery operated projector which was hand held like a torch and would project a small picture on the wall as the short length of film was pulled through it. That was just brilliant for a kid in 1947, the snag was that the only film strip we had was of the Battle of Britain with extracts from all of Churchill’s speeches.

Looking back, we had very little in those days, but we never felt in any way deprived. It was a case of not missing what you have never had, and that seems a far cry from the rampant materialism of 2015.

If you are interested in finding out more about local history, contact Southam Heritage Collection. The Collection is housed in Vivian House, Market Hill and is currently open on Tuesday mornings from 10am to 12 noon. Contact: 01926 613503 email cardallcollection@hotmail.co.uk visit our website www.southamheritage.org and find us on Facebook: Southam Heritage Collection.

Leave A Comment