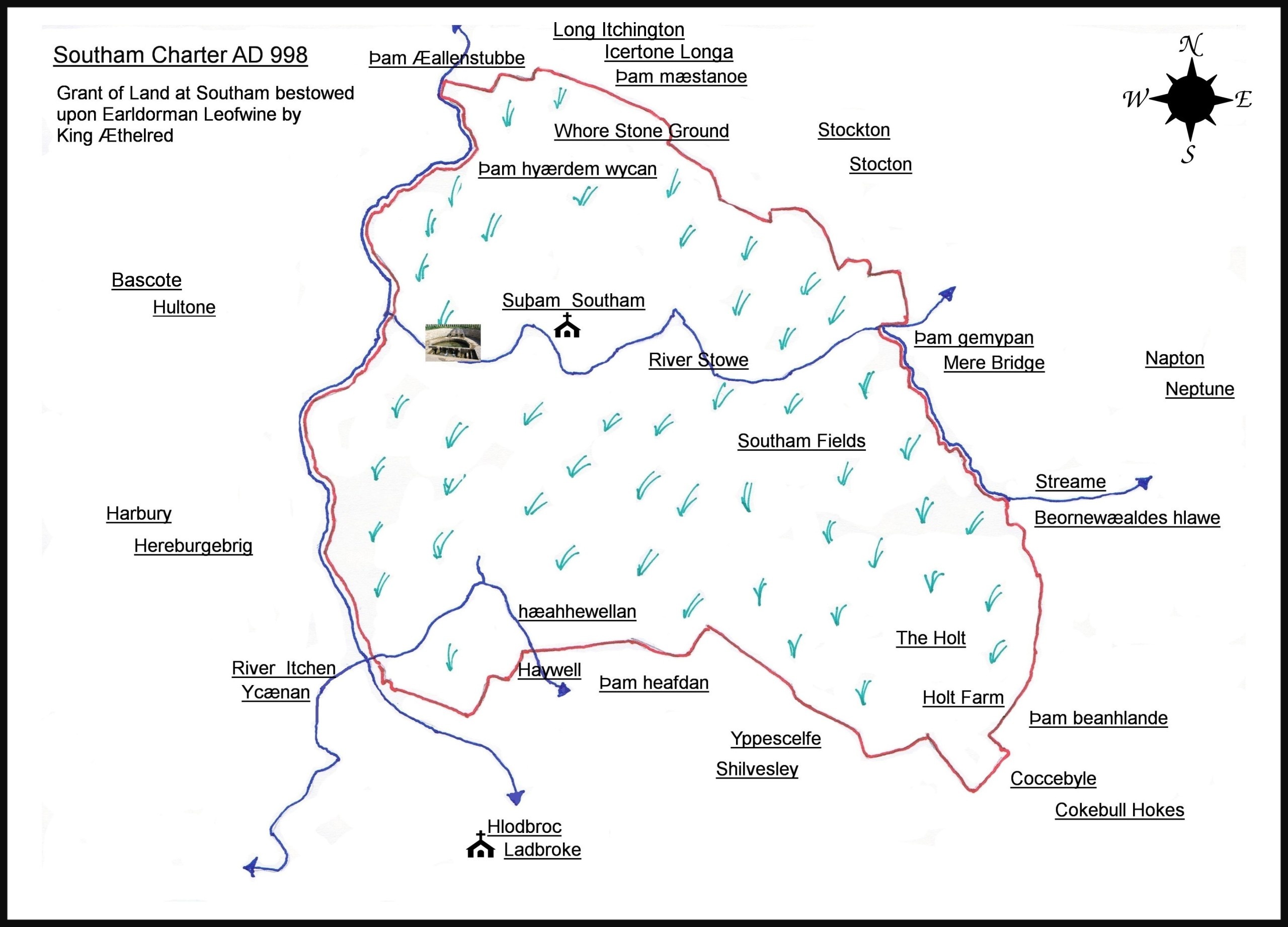

Southam town’s Charter was established in 998 AD and is of great significance as it provided a clearly defined map of its borders with its contiguous neighbours: Long Itchington, Stockton, Napton, Ladbroke, Radbourne, Harbury and Bascote. Over the ensuing centuries it has been identified as the circuitous marking of its parish.

Across time such a border has been seen as essential, as the specific knowledge of its limits, handed down over the years, decided such matters as the liabilities of citizens to contribute to the repair and upkeep of the church or the right to be buried in Southam’s churchyard. It also determined which houses and lands, especially the common fields, pastures and meadows, were in the parish. It was not unknown for boundary markers or stones to be moved into another parish.

Legally, Southam was originally a ‘royal property’ acquired by Ethelred the Unready (the name reputedly attributed as a nickname for the poor advice he received when he was younger) in a Charter in 998 AD, who in turn, granted it to Earl Leofwine, his ‘faithful duke’, when Coventry Monastery was founded in 1043. Leofwine’s son, Leofric, included it in his original endowment of Coventry Priory in 1043. The Charter was to determine the boundary of what was to become the vill (or manor) of Southam (see map). The natural and artificial features in the landscape were all named by this time, for example, the ‘yaenan’ was the name given to the River Itchen, while the spring water was the Haliwell, now Holywell. The subsequent Domesday Survey assessed the area as having about four hundred and eighty acres (four hides). The woodland was said to be a league long and half a league broad (about three miles by one and a half miles, although another measure at the time would have been rather vague, a three hour walk by a one-and-a-half hour walk.) Whichever of the measures used, it would seem to stretch well beyond what we would recognise today.

The Charter of Southam, written in 998 AD, established the first definitive boundary of Southam. Translated from Anglo-Saxon, it defines the circuit of the bounds. The Charter is held by the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

The Charter has significance in that it provides a link with the boundary representing the current parish bounds. In Anglo-Saxon times it represented a symbol of the relationship between Ethelred and his favoured and loyal Earl Leofwine. In turn, it also established the latter’s own power, position and loyalty to the king and, as in later times, established his responsibility for the law, rights and relationships with his own minor nobility, freemen and serfs.

© Oxford, Bodleian Library Hist. Ms Eng. hist a.2.

Southam Land Charter 998 AD

The original area of land that was to form the Charter was possessed by one ‘Winstan’ but taken from him by King Ethelred because he had committed murder.

The Southam (su’ham) Charter of 998 AD was initially written in Latin before reverting to Anglo-Saxon to describe the circuitous route making the bounds. It also contains the charters for Ladbroke (hlodbroce) and Radbourne (hreodburnan).

The Charter begins with an endorsement: ‘…this is the land-book of su’ham and of hlodbroce to hreodburnan.’

It then uses a Christian symbol ☧, with the invocation: ‘…in the name of the Almighty who governs and guides us…’ and calls for God’s blessing on the gifts in question, continuing:

‘…Hence I Ǣ’elred (Ethelred) with the support of the Almighty God, King of the English and other peoples in the land, give to the care of Leofwune ealdorman (my faithful duke) 7 ½ hides in the three vills, in su’ham 3 hides and in hlodbroce and hreodburnan 4 hides, and between them half a hide, to hold and to enjoy for perpetual inheritance, for as long as the light shines upon the earth…’

The document, reverting to Anglo-Saxon, then describes the boundaries of the vill of su’ham, beginning in the south west.: ‘…from where the hlodbroce falls into the ycænan’ (River Itchen), following the stream to the ‘am hyerde wycan,’ to the herdman’s wick, a farming area to the north of the vill. From the ‘wick’ the journey continues to the elder stub (ællenstubbe) and then am mærstane at the boundary with Long Itchington (icetone longa) on what is now the Coventry Road. The mærstane was the boundary stone in a field believed to have been called the ‘whore stone ground’, at the border junction of Southam, Stockton (stocton) and Long Itchington, possibly in the region where the cement works is now. The stone itself is long gone, although a fragment is believed to lie on Stockton Green.

The route then leads from the boundary stone to the confluence of the River Stowe and a stream near the north east corner of the vill at Myers Bridge (pæm gemyþan/myerbrygge). It then follows the stream to the ‘beornewæaldes hlawe,’ the boundary running south-east upstream where there was possibly a tumulus at the ‘hlawe’ on the eastern boundary. From the ‘hlawe’ it travels ‘…to the pit (þā pytte) and up to the þā beanhlande,’ beanlands where the land rises southward to an area later known as flaxland.

The route continues to run to the extreme south-east beside the Banbury Road to Cokesbull Hokes ‘coccebyle’, the cock’s bill. This is the projection of the current parish, the name referring to a land unit. Beside it lies the Holt/Holt Farm, once a wooded area supposedly the home to wild animals.

At the very corner, the route runs north-westwards for a short space and then turns westward ‘to yppescel’ (Ippa’s shelf), which is a ledge of the high land of Ladbroke Hill, near the southern boundary with Southam. Then, from Ippa’s shelf, following the headland to the high spring across to ‘hæahhwwellan’ (Haywell – not to be confused with Southam’s Holy Well) and from the spring to hlodbroce following the brook again to the Itchen, ‘yoænon.’

The River Itchen is itself the boundary marker, so the route continues northward along it once again. The Charter then continues with a similar description of the boundaries of Ladbroke and Radbourne.

The Charter ends, again in Latin with: ‘…This Charter was drawn up in the year of Incarnation of Our Lord DCCCCLXXXXVIII.’

There is a list of witnesses to the gift, including Æþelred, King of England, Ælfric, Archbishop of Dorchester and Wulfstan, Bishop of London.

Leofwine, Alderrman of Mercia, was the father of Leofric, later the Earl of Mercia, who founded the Benedictine Monastery at Coventry in 1043 and endowed it with twenty-four vills, including Southam. The boundaries of the town and parish are in the Coventry Chartulary of 1410. The Priory remained the sole Lord of the Manor until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell.

The document provides a legal writ, a ‘bookland’, of the rights of land and the boundaries of the new estate, which is witnessed (although not signed) by many nobles and churchmen. It is interesting to note that the Charter contains a sanction which affirms that God will punish those who violate the grant of the estate. Clearly, Ethelred thought a great deal of Leofwine.

The custom of ‘beating the bounds’ was witnessed in Southam as early as in Anglo-Saxon days, and by Tudor and Stuart times, parishioners were obliged by common law to secure the legal bounds of the parish.

Also known as a perambulation or ‘gangsday,’ the event took place in May, after the field seed had been sown, when villagers, usually led by the rector and churchwardens, took part in the Rogation procession around the bounds of Southam, singing litanies, psalms and reciting prayers as a blessing on the new crop and harvest. In some respects, it follows the pagan ritual from Roman times when farmers and villagers would celebrate the gifts of the deity Ceres, goddess of grain, crops and fertility, often with a sacrifice.

In Southam, the aim of the procession was the ‘swatting’ of local border landmarks with green boughs of willow or birch by groups of boys in order to establish a shared mental map of the land.

In Elizabethan days the journey was of such a serious nature that the rector and churchwardens were ordered by an injunction to stop the journey at certain places (perhaps at Myer – Mere – Bridge on the Napton road, or at Elder-Stub on the border with Long Itchington, or at Herhhewellan – Haywell – on the Ladbroke border) and admonish the people to give thanks to God whilst the rector invoked such sentiments as: ‘Cursed is he that transgresses the bounds or doles of his neighbours.’

As a part of the celebration, the churchwardens of Southam in 1617, Thomas Harris and Timothy Jackson, under the rector, Francis Hollioak, were responsible for the provision of bread and ale to refresh the walkers on their trek. Evidence of this is provided by the Southam Churchwarden’s Accomptes and Notices which included:

1617: paid bread and beer at the procession 0 10s 1d

1619: paid for provisions when they went to the procession 0 111j v1j

1625: paid for bread and beer at the procession 0 11s 111d

1629: paid for bread for the procession 0 11s 0d

One lasting myth related to the perambulation, whether it applied to Southam or elsewhere, was the claim that:

‘…in order that the boundaries of the parish might be indelibly impressed on the mind of the younger portion of the community it was deemed advisable to bump some promising boy (perhaps the banging of the head), painfully against the boundary stones; or better still, to public whip him while he strove to impress on his memory the exact position of the same land marks.’

(William Andrew: Curious Church Customs, 1895).

Even if paid 1d (or perhaps the modern-day equivalent) for their troubles, I doubt there would be many volunteers from Southam youngsters of today!

Southam town and parish boundary established by the Charter of 998 AD

Leave A Comment