‘The Great Storm of 1703’ was of unusual, tremendous ferocity, probably passing in intensity all the storms ever known in Great Britain. It was the most terrifying and catastrophic storm ever recorded here. During the night of 26th-27th November 1703, widespread devastation was caused to many parts of the Midlands, East Anglia, the south of England and south Wales. How it developed is still the subject of debate; it may have begun life as a tropical hurricane.

The Gregorian Calendar was not introduced until 1782, but had it been in use in England at that time, the two peak days of the ‘Great Storm’ would have been dated 7th – 8th December. The storm appears to have started on 19th November, not abating until 2nd December. It caused colossal damage, killing as many as 10,000 people. Waves 60 feet high lashed the coastline. Destructive gales raged with persistence and fury. Whole communities were demolished; around 8,000 people died in the floods. People did not know whether to stay indoors and chance the building collapsing on them, or risk flying wreckage outside.

Queen Anne believed the storm was ‘Retribution sent by God’, a token of ‘Divine Displeasure’, a ‘Calamity of this sort so Dreadful and Astonishing, that the like hath not been Seen or Felt, in the Memory of any Person living in this Our Kingdom.’

The writer Daniel Defoe, author of ‘Robinson Crusoe’, advertised in the ‘London Gazette’, inviting people to send him eye-witness accounts of how the storm affected their communities, recording these in his book ‘The Storm’, published in July 1704, ‘The Greatest, the Longest in Duration, the Widest in Extent, of all the Tempests and Storms that History gives any Account of since the Beginning of Time’.

In Warwickshire, the villages and towns of Leamington Hastings, Marton, Meriden, Stratford-upon-Avon, Wellesbourne and Southam, suffered badly. In Marton, a huge rick of wheat was lifted up, transported by the wind in its entirety and set down twenty yards away.

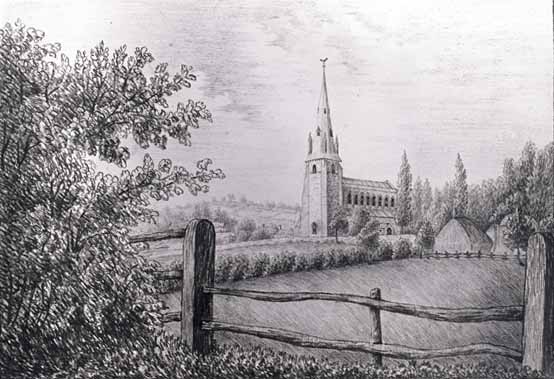

Many repairs were needed to Southam church including to the steeple, shown in the Southam churchwardens’ accounts now held in Warwickshire Record Office, when ‘anparitors’, or ‘paritors,’ (summoning officers of an ecclesiastical court), were called out to look at the damage.

Southam churchwarden’s accounts December 1703

“Payd for the Parritor for the forme of prayer for the wind.” 0-1-0 (one shilling)

Southam churchwarden’s accounts on January 7th 1704

“Payd to the Parritors.” 0-1-6 (one shilling and six pence) “A ……(illegible) of prayers & work mason for fast.”

Further work was recorded on February 8th 1704

“Payd for work Glazing the church.” 0-15-0 (fifteen shillings) and 0-18-7 (eighteen shillings and seven pence) was also paid for other work to the church.

Plus, a further 0-9-0 (nine shillings) “For mending the bell, benches and bell wheels.”

In a ‘Tale of the Tub’ by Jonathan Swift published in 1704, ‘a large skin of parchment’ is referred to, serving as an ‘umbrella in rainy weather’; however, it would not have been much use with the violent winds recorded in the Great Storm.

© Jill Prime primulacov@yahoo.co.uk

The photograph shows Southam Church and a Hay rick, and is from a drawing by Sarah Day. If you are interested in finding out more about local history, contact Southam Heritage Collection. We are located in the foyer of Tithe Place (opposite the Library entrance) in High Street, Southam and are normally open on Tuesday, Friday and Saturday mornings from 10am to 12 noon. Contact: 01926 613503 email southamheritage@hotmail.com visit our website www.southamheritage.org and find us on Facebook: Southam Heritage Collection.

Leave A Comment